I was the first player drug-tested in baseball, and I am the one who asked for it.” – Babe Dahlgren

The Baseball Writers Association of America’s stance on The Steroid Era is well-known. They have made that very clear. There are folks on both sides of the issue. Many feel that the lack of evidence supporting the exclusion of players like Mike Piazza and Jeff Bagwell from the Baseball Hall of Fame based on rumors that they may have used PEDs, is an injustice.

We also live in an era where it is hard to imagine people choosing integrity over the millions of dollars to be made with the popping of a pill or the injecting of a needle. These players may indeed be innocent, and if they are, they have the power, resources and platform to defend themselves.

Some other players never got that opportunity.

There was another player who once took a drug test, the first one in known baseball history. It was paid for by then-MLB commissioner Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, and it came back clean. For some reason, Landis and several of the commissioners that followed him, refused to make the results public, or provide that player with some level of justice.

Instead, former MLB All-Star Babe Dahlgren, once considered the best fielding first baseman in baseball, was sentenced to a life as a baseball vagabond. Even after his playing days, he was plagued with the inaction of a baseball industry that had turned its back on him a long time before.

The whole story is chronicled in the book, Rumor In Town: A Grandson’s Promise to Right a Wrong, written by Dahlgren’s grandson, Matt Dahlgren.

Sadly, two of the most respected figures in baseball history played a large role in Dahlgren’s misery, and it is perhaps that reality which is responsible for the lack of coverage and discussion of these events.

From Gotham Baseball’s Spring 2011 Issue, “Going Nine: The Other Babe”

“The guy can do everything, and I have a hunch that he invents plays as he goes along. If an old-timer were to swear to me on a stack of testaments that there was every a greater defensive first baseman than Ellsworth ‘Babe’ Dahlgren of the Yankees I wouldn’t believe him.” John Lardner, The New Yorker, June 13, 1940

According to Matt Dahlgren, Babe was also the victim of a vicious rumor; he was a marijuana smoker. Mike Lynch of Seamheads.com summarized it best, stating that the rumor was “started by a Hall Of Fame manager, perpetuated by a Hall of Fame executive, and buried by a Hall Of Fame Commissioner.”

Dahlgren started his career in the Boston Red Sox farm system and was poised to become the team’s first baseman until the Bosox acquired the Philadelphia A’s slugger Jimmie Foxx. It seemed a trade to another team made the best sense. However, he was dealt to an even worse situation; the Yankees, where Lou Gehrig was entrenched. Determined to prove that he belonged, Dahlgren took his game to the Yankees’ top farm team in Newark in 1937, where he hit. 340 for the Bears, one of the greatest minor league champions in baseball history.

He would make the Yankees in 1938 as a utility man, but played in just 27 games, mostly as a pinch-hitter. In 1939, he would make the most of an opportunity he desperately wanted, he just hated the way it happened.

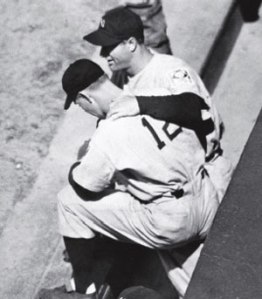

Replacing Gehrig, Dahlgren hit a home run, a double off the top of the fence and two drives that were caught against the fence in a 22-2 rout over Detroit.

“I especially admired Gehrig because he was a first baseman like me,” Dahlgren told Newsday’s Joe Gergen in 1988. “I never dreamed one day I’d be in New York to take the man’s place.”

He would hit only .235 that year for the Yanks, but he would hit 15 home runs and drive in 89 runs batting seventh or eighth in a powerful lineup. In the World Series that year, Dahlgren would hit his only World Series home run, helping the Yankees sweep the Reds. The future looked bright for the 27-year old Dahlgren. Then he went home to San Francisco, and his life would never be the same.

According to the book, Bay Area legend Lefty O’Doul hated the fact the Joe McCarthy, and not he, was the manager of the New York Yankees. He was often telling anyone who would listen that “Ol’ Marse Joe” was a push-button manager and that “anyone could manage the Yankees”. An Associated Press photographer took a picture of Dahlgren receiving “batting tips” from O’Doul at an off-season workout (the reality was that they barely talked that day). Combine the cracks that O’Doul made that day to the media in attendance like, “The Yankees have to send me their players to learn how to hit.” was the killer. The Yankee manager may have been a legend, be he was also was a thin-skinned person, as well as a heavy drinker. Throw in the fact that the now-veteran first baseman was very well-liked by his teammates and the local press, there was the makings of a very bad situation.

Dahlgren had another solid year in 1940, hitting .263 / 12/ 73, and played a brilliant first base, but when the Yankees did not win the pennant. McCarthy seemed to blame Dahlgren, citing a key error down the stretch that cost the Yankees a ball game.

He was sent to the Boston Braves in 1941, was dealt midway in that season to the Cubs, where he really played well, hitting .263 / 23/ 89 for the season. While Dahlgren was having the best year of his career to date, McCarthy was telling the New York sportswriters – who all liked Dahlgren and thought he was a superb first baseman and were watching Johnny Sturm hit just .235 with no power and nowhere near the glove – that Dahlgren’s arms were too short to play first base.

Really.

The longer the season wore on, the longer it looked to the media like McCarthy must have had a personal beef with Dahlgren, and the writers pressed McCarthy on the trade. Now, remember, it was the 1941 season, and Joe DiMaggio was setting his magical streak and Ted Williams was hitting .406 for the Red Sox. Though sad he had left the Yankees, Dahlgren was happy in Chicago, playing well and finally getting the accolades he deserved.

Then, almost instantly, Dahlgren would spend the rest of his career as a talented and mysterious vagabond. In 1942, he would get traded from Chicago to St. Louis to Brooklyn (where Branch Rickey would accuse him of smoking marijuana, the first time Dahlgren would hear of the rumor) to Philadelphia (where he became an All-Star) to Pittsburgh (where he would drive in 101 runs and hit .289 in 1944) and finally back to St. Louis, where he would finally be discarded.

In the midst of the incredulous rumor, Dahlgren informed then-Commissioner Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis of the rumor, and the Judge, according to the book, paid all the expenses for what would prove to be a “clean” drug test for Dahlgren. But Landis and every subsequent Commissioner – up until his death in 1996 – failed to address Babe’s cause.

Dahlgren also died not knowing who had started the rumor. He had always assumed that it was Rickey, because of the way the situation had played out. It wasn’t until his grandson Matt, who wanted to write the manuscript that would become “Rumor in Town” (Babe’s original manuscript, as well as a letter from Landis proving the rumor existed, were lost in a fire at Babe’s home in 1980), that the origin of the rumor surfaced.

Dahlgren was doing research for his book when someone suggested that Marty Appel, arguably the preeminent Yankees historian, might be the person to provide stories about his father.

Appel told him about a conversation he had with New York Times sportswriter John Drebinger in 1973, recalling McCarthy talking to a small group of baseball insiders at the end of the 1940 season. Drebinger, Appel remembered, recalled that McCarthy was griping that he Yankees would have won the pennant in 1940 had it not been for an error that Dahlgren made in a late-season game against Cleveland. leveling a blow that all but ruin a man’s career; “Dahlgren doesn’t screw up that play if he wasn’t a marijuana smoker.”

Tired of being made a fool for suggesting that the obviously proportionally limbed Dahlgren’s arms were more than long enough to play first, McCarthy decided to spread a rumor so incredible, so scandalous that few would ever repeat it. But someone did.

“Rumor in Town” might be a promise by a grandson to his grandfather to right a terrible wrong, but one would hope that it also motivate Major League Baseball or motivate the BBWAA to right a terrible injustice. To date, the case is one that MLB doesn’t feel needs to be reopened.. And that is a big a tragedy as was the rumor that cost Babe Dahlgren his career.