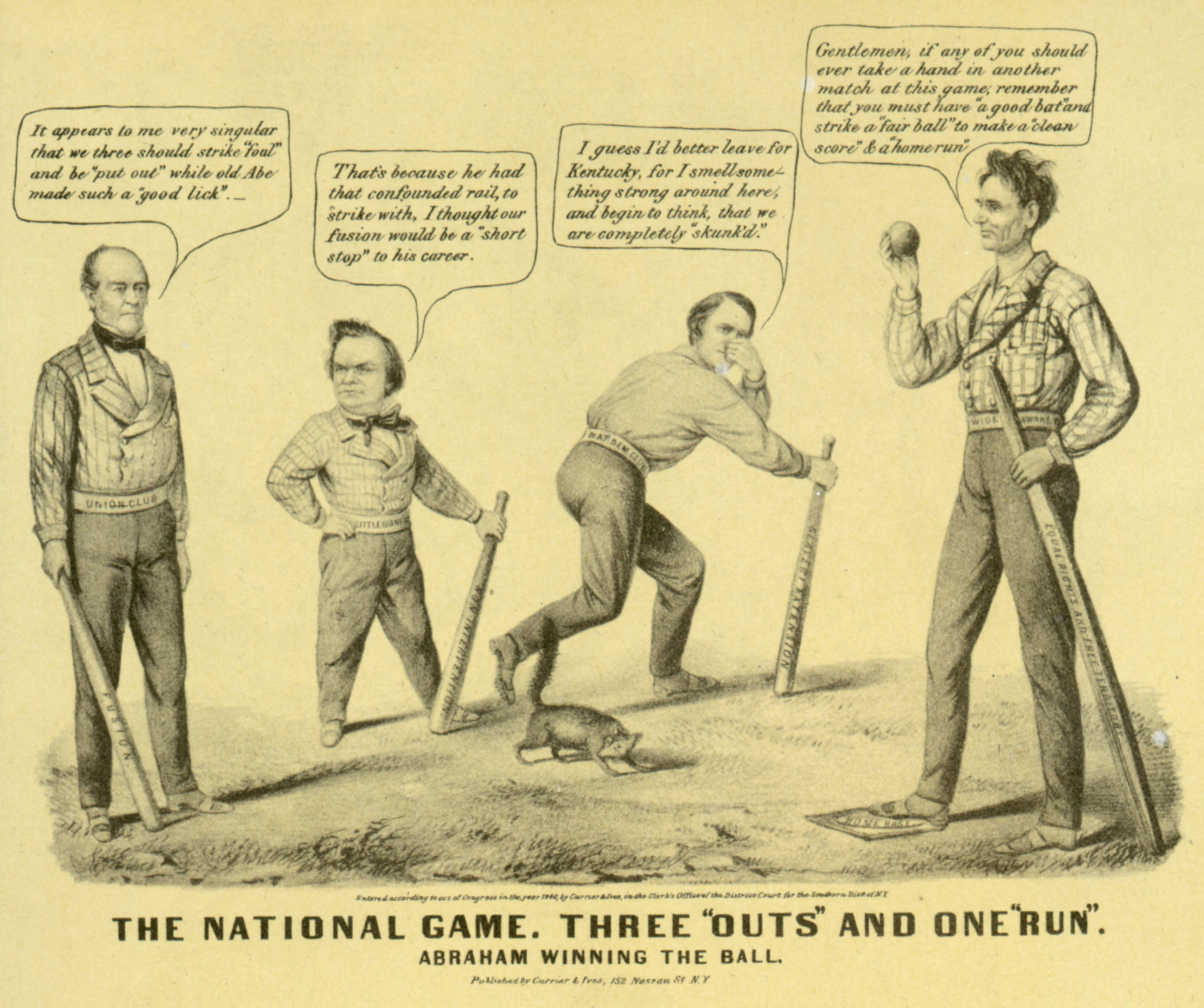

There is a famous political cartoon from the 1860 U.S. Presidential election, depicting Abraham Lincoln winning a baseball game against fellow candidates John Bell, Stephen Douglas and John Breckinridge. The Currier & Ives piece uses terminology like “put out,” “strike,” “short stop,” “home run” and “fair ball,” words that would be familiar to voters even then, 16 years before the start of the National League, which for many is considered the first major league. And while it’s not the first connection between the nation’s highest office and its favorite sport then and–for many –now, it’s a key signifier that the political game and the one between the lines are intertwined almost as long as baseball itself.

Chronicling this in an area in which he has unique dual expertise, Curt Smith manages to blend summations of Presidents who loved the game (Taft, Nixon, Carter, Bush 41 and 43), those who had no use for it (T. Roosevelt) and the one who in many ways saved it (FDR) in his thorough book The Presidents and the Pastime: The History of Baseball & The White House (University of Nebraska Press, 472 pps, $29.99). A baseball historian with 17 books to his credit, including numerous on his favorite sport, Smith also brings his intimate knowledge of the White House as a speechwriter for George H. W. Bush to tie these two national institutions together.

Smith traces the connection back to the Founding Fathers, noting that George Washington likely played baseball cousin rounders and John Adams played the game’s variant “One o’cat” as a youth. And while little is known about how the sport may have affected their presidencies, or those of POTUS #3, Jefferson, through the antebellum lot of Polk, Tyler, Buchanan, et al, these were the years of the game’s development, one that was nearly stifled as the 20th century dawned by Theodore Roosevelt, who showed probably the most disdain for the game among all who held the office, preferring football, boxing, tennis and other sports he deemed more violent (tennis?).

It was Theodore’s fifth cousin and future White House denizen FDR whose master stroke of a pen kept baseball alive during World War II, not excepting players from service but allowing the game to continue in the famous 1942 “Green Light Letter” to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, to offer Americans “…a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before.”

As the 20th century moves on in the narrative, Smith delves deeper into the relationship between the Presidents and the game during their respective terms. His affection for Eisenhower, Reagan and both Bushes abundantly clear, Smith still records the Democratic White House occupants’ connection to the sport over that span, noting Jimmy and Rosalind Carter’s enduring love of their home state Atlanta Braves and though Bill Clinton’s dedicated chapter has almost as many references to his predecessor as to Clinton, does note the Arkansas native’s ties to the sport through Cardinals fandom dating to his early days.

The Presidents and the Pastime is ultimately very satisfying, on the one hand a primer—or reminder—of the notable events (and sometimes scandals) of each administration, and on the other an examination of the changes in the game throughout the last 110 years, in particular. From Reagan’s game recreations on Des Moines radio to Nixon’s “Dream Team” selections to Taft’s first pitch and inadvertent original “seventh inning stretch,” Smith details it all in a book The Gipper would surely be proud of.