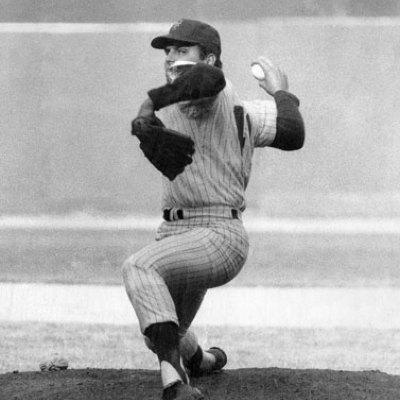

“I have a plaque up in Cooperstown that’s across from Walter Johnson and Christy Mathewson, And when they lock up the place, we sit down and have a beer.” – Tom Seaver

Despite putting the Mets on the map, the people who run the Mets — past and present — rarely did right by The Franchise.

Back in 2016, the wife of the greatest player to ever wear the orange and blue was disgusted.

“I’m embarrassed for (the Mets). I really am,” Nancy Seaver told The Daily News, referring to the fact that the New York Mets had failed to honor her husband Tom in a manner befitting the Hall of Fame pitcher.

That was four years ago.

George Thomas Seaver passed away on Aug. 31, and I’m more than embarrassed. I’m outraged.

Every baseball fan I know has that one player they love above all else. For my dad, it was Duke Snider, my son Jack’s was Jose Reyes, and for my cousin Dominick it was Thurman Munson.

My all-time favorite is Tom Seaver.

That’s how I started the Tom Seaver chapter in my book, Gotham Baseball: New York’s All-Time Team.

As I mention in that chapter, when I started writing the book, I learned that Seaver was no longer doing interviews and would soon be retiring from public life.

Despite that news, I still wasn’t prepared when I heard the news that the greatest Mets player who ever lived had died at the age of 75. In fact, I was stunned and speechless. If you know me, you’d know the latter is a rarity.

Then I was truly sad. I sent out a flurry of tweets that night, expressing my heartbreak at the loss of Seaver, my first sports idol. As I wrote, I was instantly taken back to my bedroom in Brooklyn, trying to listen to the portable radio hidden under my pillow to games he pitched. I went through my memory bank, trying to reconstruct the games I had seen him pitch in person at Shea Stadium, but the lens was a little blurry; we normally sat in the upper deck. My more clearer memories were watching the games on TV with my dad, something we did on a regular basis.

As the hours passed and people shared their memories, then I happened to see a statement from Fred and Jeff Wilpon:

Tom was nicknamed ‘The Franchise’ and ‘Tom Terrific’ because of how valuable he truly was to our organization and our loyal fans, as his #41 was the first player number retired by the organization in 1988. He was simply the greatest Mets player of all-time and among the best to ever play the game which culminated with his near unanimous induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1992.

Very quickly, I became angry. My first thought was, “spare us your platitudes, your actions peak far more loudly than your useless words.” But I thought better of it, and simply stepped away from social media for a day.

I needed some time to collect my thoughts, and really delve into how tragic it was that Tom Seaver was treated so terribly by the men who have run the Mets.

Let’s start at the beginning of this hateful relationship the Mets’ ownership had with “The Franchise.” After the Mets’ owner Joan Whitney Payson died on Oct. 4, 1975, whatever rein she had on her chairman of the board M. Donald Grant was finally snapped. Grant had always had a tenuous relationship with all of his players (and the rest of the baseball people), but eyed Seaver with jealous contempt.

Grant, who once told sportswriter Jack Lang, “Don’t call Seaver ‘The Franchise’ because Mrs. Payson and I are the franchise,’ hated that Seaver was cerebral and spoke his mind to the press. He even called his ace a Communist.

“Trade [Tom Seaver]? One does not dispose of a Picasso for a schoolboy drawing in a moment of blister.” – Maury Allen, New York Post, June 10, 1977

I remember the dark day in 1977, after he was traded, the Daily News front page blaring “Seaver To Reds.” In my book, I tried to piece together the groundwork that led to the insanity that followed:

During the owner’s lockout in the spring of 1976, Seaver took a leadership role as a union rep, and Grant was incensed. In a wonderful piece written for Harper’s following the trade, A. Bartlett Giamatti — who would later become the Commissioner of Baseball — wrote, “[Grant thought] Tom wanted too much. Tom wanted, somehow, to cross the line between employee and equal, hired hand and golf partner, ‘boy’ and man. What M. Donald Grant could not abide—after all, could he, Grant, ever become a Payson? Of course not. Everything is ordered. Doesn’t anyone understand anything anymore?”

Seaver was vocal about his contract, yes. But he also wanted the team to be the best that it could be.

“The money was always secondary to my loyalty to the Mets,” Seaver told Sports Illustrated’s Kent Hannon in 1977. “The people who think I was bitter about not making more money or who think I was trying to force a trade by asking that my contract be renegotiated won’t believe me. But for the record, my loyalty to the Mets and my desire to make them competitive always came first. I don’t think I’ve shown myself to be a greedy person.”

In the end, with the help of a number of caustic columns by Dick Young — whose son-in-law Thornton Geary was working for the Mets — Seaver demanded a trade, and was sent to the Reds. We all know what happened after.

“With him, it was a matter of loyalty,” Nancy Seaver told Sport Illustrated’s Frank DeFord in 1981, referring to the “Midnight Massacre” deal that sent Seaver to Cincinnati. “And his loyalty was thrown into his face. Tom was hurt badly. I don’t think, even now, he’d like to admit how much. He wanted to live and die at [Shea Stadium]. And they jilted him.”

For years, I yearned for Seaver’s return, never imagining it could happen. As the Mets reached new lows from 1978-1982, I watched from afar as he tossed a no-hitter — his only one — in a Reds uniform. Seaver should have been a final piece for the Big Red Machine, but the team that had Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan and Tony Perez (and that jerk Pete Rose), couldn’t get past the Dodgers in 1978, the Pirates in 1979 or the split-season rules in the strike year of 1981 (best record overall in NL West, but finishing send in each half of the season).

Nevertheless, Seaver had a solid six years with the Reds, good enough to land him in the Reds Hall of Fame. (I still think he got robbed by Fernandomania in the 1981 Cy Young Award voting.)

Then, we got him back.

Then, we got him back.

I tried to describe the euphoria in the book:

Opening Day 1983 at Shea Stadium, I remember it as colorful as the moment when black and white Dorothy Gale first peeked outside the door at the full color Land of Oz.

In truth, I watched Opening Day at Shea Stadium in 1983 on a 12-inch black and white TV my dad had re-claimed on his NYC Department of Sanitation route. But I remember it in full color, not truly believing it was really happening. The roar of the crowd when PA announcer Jack Franchetti said, “batting ninth and pitching, now warming up in the bullpen, Number 41.”

The best player to ever wear the orange and blue was back, and all that was good was so again. He struck out Pete Rose (who I disliked immensely) to start the game, and the cheers were even louder.

It wouldn’t be a banner year for the Mets, they would finish 68-94, manager George Bamberger would quit in June, but they would also get Keith Hernandez later that month in a trade, and Darryl Strawberry made his debut; winning Rookie Of The Year …

Seaver’s record was just 9-14, but at 38, he still led the team innings pitched (231), ERA (3.55), FIP (3.77) and WHIP (1.24).

After the season, Nov. 3, 1983, to be exact, the late, great Dave Anderson wrote in his “Sports Of The Times” column in The New York Times that Seaver would be “the unofficial pitching coach” for the 1984 Mets.

While the Yankees keep searching for answers to questions George Steinbrenner has not yet asked, the Mets lead New York’s baseball off-season in optimism. At least the Mets know their manager next season will be Davey Johnson, and they know that Tom Seaver will be not only their opening-day pitcher April 2 in Cincinnati but also their unofficial pitching coach. That was the unofficial title that Davey Johnson bestowed on Seaver yesterday after the Mets had announced that they had picked up the option for next season on their 39- year-old right-hander, who will earn $750,000.

”Regardless of who I hire as a pitching coach,” said Davey Johnson, who is seeking Mel Stottlemyre, the one-time Yankee right-hander, for that job, ”I would like Tom to be an unofficial pitching coach. If the younger pitchers pick up his work habits without me forcing it on them, we would be in much better shape.”

… [In 1983] When he tried to help some of the Mets’ young pitchers in spring training, his philosophy conflicted somewhat with that of George Bamberger, who was one of baseball’s most respected pitching coaches with the Baltimore Orioles before he departed to manage first the Milwaukee Brewers and then the Mets …

He already has an idea of what five young Met pitchers need in order to develop into a winning staff. The five are Walt Terrell (8-8 this season), Scott Holman (1-7), Ron Darling (10-9 at Tidewater, 1-3 with the Mets) and Tim Leary (8-16 with Tidewater, 1-1 with the Mets), all right-handers, and Carlos Diaz (3-1), a left-hander.

”Terrell is a real bulldog, he won’t give you an inch, the kind of guy who can win 15 games,” Tom Seaver said. ”He’s got a good sinker. He’s the kind of guy you need in the middle of a rotation, a third or fourth starter you can depend on. And he helps with his bat.

”Holman has an outstanding curveball. He also has a better fastball than he thinks he has, because he’s had arm trouble, a good sinking fastball. He didn’t pitch for 20 days last season, so he needs help with his confidence now. But he can be a good pitcher.

”Darling has the best stuff, physically, of all the young pitchers. He needs innings. You’ve got to put him out there and let him struggle through it. He’s intelligent, he wants to learn, he wants to pitch. If he develops, he could win 12, 15 games next year.

”Leary has excellent physical stuff. But after the arm trouble he had at the start of the 1981 season, he has to learn to trust his arm again. I didn’t see him before he hurt his arm. I’m told he was amazing. But he needs to work on mechanics on his upper left side.

Tom Seaver has yet to see the most touted of the Mets’ young pitchers: Dwight Gooden, a right-hander who will be 19 years old in two weeks. With Lynchburg, Va., in the Class A Carolina League this year, he had a 19-4 record, a 2.50 earned run average and 300 strikeouts in 191 innings. He walked 112 but allowed only 121 hits. Promoted to Tidewater for the Minor League World Series, he stopped Denver, 4-2, on a four-hitter with six strikeouts and three walks.

”You just look at his numbers at his age, you know he’s got a lot of potential,” Tom Seaver said. ”If he can put it all together, he can be a 20-game winner in the big leagues someday.”

Then, on Jan. 20, 1984, the Mets did it again. Tom Seaver was gone, selected by the Chicago White Sox in the free agent compensation pool because then-GM Frank Cashen chose not to protect his 1984 Opening Day pitcher.

Cashen said it was a mistake, but I have never bought into that theory, as I detailed in the Seaver chapter. In my opinion, Davey Johnson, who would be a rookie manager in 1984, didn’t want a future Hall of Famer on his roster.

Among the players the Mets protected? Thirty-two year old and injury-prone Craig Swan, coming off a terrible 1983 season; 2-8 with 5.51 ERA. Davey would cut Swan by May 9 the next year.

[Fred] Wilpon, who conveniently was a good friend of White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, certainly could have suggested the White Sox might benefit from having a guy like Seaver around.

Do I have any on the record confirmation of this? I do not.

All I can offer is this: On Dec. 14, 1982, the New York Times’ Dave Anderson quoted Seaver — who was about to rejoin the Mets — as saying “looking to the future, I think I would like to run a ball club in the front office or manage on the field.” In the column, Anderson called Seaver, once he decided to retire, the next manager of the Mets.

In 1985, with the Mets trying to get past the Cardinals in the NL East, Cashen told Davey Johnson that he had a chance to get Seaver, and Davey said no. That’s according to Davey’s book ”Bats,” (Putnam, 1986), in which Johnson notes that Cashen told him Seaver was available, and the Mets’ manager didn’t want the pitcher who had once been the ”franchise” at Shea Stadium.

When told about the passage in Davey’s book, Seaver told The New York Times he wasn’t surprised. ”I’ve heard from other sources that Davey wasn’t too hot about having me around.”

Hindsight is 20-20, as they say, but maybe a pitcher like Dwight Gooden could have benefitted by having a legend like Tom Seaver around, because accordinging to Tony LaRussa, it certainly helped the White Sox.

“We didn`t know if he would act like he was Tom Seaver, act like he deserved to be treated like he was Tom Seaver,” then-White Sox manager LaRussa told The Chicago Tribune in the spring of 1985. ”His attitude was perfect. His record and reputation meant nothing compared to the team good. He puts that first. For me to just write his name on the lineup card is an honor for a manager.”

In 1984, Seaver went 15-11 with a 3.95 ERA, 236 innings and a 1.17 WHIP, which would have placed him second in wins and WHIP to Gooden and first in innings. Mets finished second in the NL East, six games behind the Cubs.

Good thing they protected Swan.

In 1985, Tom was even better, 16-11 with a 3.17 ERA, 238 innings and a 1.22 WHIP. Mets lost the NL East by three games to the St. Louis Cardinals. Think he would have been a better option in the rotation than Ed Lynch?

Seaver was on the 1986 Red Sox, but didn’t pitch in the World Series (thank God), and got one last chance to return to the Mets in 1987, but only after Dwight Gooden’s cocaine problem surfaced and Bob Ojeda’s landscaping accident had the Mets sending guys like Don Schulze to the mound to defend their World Series title.

Seaver tried to pitch himself into shape, but it wasn’t meant to be and retired.

Two years later, he returned to baseball, in the broadcasting booth.

Only a team that hates its greatest player — and its fans — would have allowed this infamnia to happen. It convinced me even more that Fred Wilpon helped grease the wheels for Seaver to go elsewhere in 1984.

I’ll say it again. Infamnia.

Seaver would eventually return to the organization in 1999, and (of course) it was Nelson Doubleday who engineered it.

According to The New York Times, “Seaver’s agent Matt Merola, called Nelson Doubleday, the Mets’ co-owner, and, according to Seaver, asked, ‘’Why isn’t Tom involved in your ball club one way or another?”

Imagine that.

In a move that Seaver said was long overdue, the Mets brought back their Hall of Fame pitcher to serve in a variety of roles, most visibly as one of their announcers for the 50 games this coming season and the 40 games next year that will be televised by Channel 11. Under a two-year contract, Seaver will also work for the Mets in uniform, beginning with a 10-day period in spring training and continuing throughout the season as an organization-wide pitching guru.

”I don’t want to be the general manager, the manager or the pitching coach,” Seaver cautioned during a conference call with reporters.

He added: ”I wonder why it didn’t happen five or six years ago. I’m just glad we’ve been able to get me back and get me involved. I feel I can help the organization in many aspects. I think I’m capable of doing that.”

For a few years, we had The Franchise back. I especially cherish listening to him for the Piazza Era. Listening to Tom and Ralph Kiner was a great way to watch a ballgame.

Seaver retired from broadcasting in 2005, wanting to fulfill his dream of owning a vineyard. I think his broadcasting tenure in New York did not really work out as he envisioned, and while I don’t doubt he really wanted to raise grapes, perhaps had Fred Wilpon treated Tom Seaver even a little bit the way he does Sandy Koufax, maybe Seaver would have stayed more connected with the team.

As plans for what would become Citi Field began to take shape, there was little — if any– talk of how Seaver would be honored in the team’s “fancy-dancy stadium” (Doubleday always wanted to renovate Shea Stadium in a baseball-only ballpark the way the Angels did with Angels Stadium in 1998).

When it became known that the new ballpark would be a replica of Ebbets Field, most of us fans were okay with that. My dad, who is the same age as Fred Wilpon, was a Brooklyn Dodgers fan and he loved the idea.

But when the plan to use the rotunda to honor Jackie Robinson was revealed, my first reaction was why? In 2005, Fred had already erected a statue of Jackie and Pee Wee at then-KeySpan Park in Brooklyn, which was fitting. That’s where the Brooklyn Cyclones play, and it was a perfect place to celebrate the borough where “42” changed history.

The Wilpons have always been tone deaf when it comes to their fan base, and no one put it better than Matt Balasis on the excellent Mets fan-driven website, metsmerizedonline.com

Our unique identity — born from the modernist intonations of the 1964 Worlds Fair — not only stands apart from old New York baseball culture, it is in many ways diametrically opposed to it. The Mets are all that is new and different, quirky and inventive, and of course, charming.

The Mets are lovable in losing, and occasionally boisterous and unstoppable. They are Tom Seaver and Cleon Jones and Tug McGraw and Lee Mazzilli and Strawberry and Doc Gooden and many other wildly talented players. Wilpon believed he could superimpose his own perceptions on the franchise rather than allow the fans to drive the team’s culture and heritage.

The Dodger-inspired edifices and rotundas of Citi Field may seem like passing slights to the team’s true character, but they point to an owner who is hopelessly out of touch. It is difficult to envision how these owners, given their history, could possibly prevail upon whatever faculties are available to them to bring about a Met renaissance. Much like Gatsby, no amount of lavish parties or helicopter rides during spring training will convince anyone that they are legitimate to their ambitions.

The lack of any history for the New York Giants in Citi Field, the favorite team of Mrs. Payson before she became a visible and die hard Mets fan herself (does that interlocking NY cap look familiar?) and Willie Mays is glaring as well. The Mets played in the Polo Grounds for goodness sake! The missed opportunity to embrace BOTH of New York’s National League teams was one of the greatest failures of Fred Wilpon’s dream to rebuild his childhood.

The rotunda should have been named for Gil Hodges, the true bridge from the Brooklyn Dodgers that Fred Wilpon loves, to the 1962 lovable losers and finally, as manager of the Amazin’ Mets of 1969. Instead of a giant 42 in Dodger Blue inside the rotunda, there should have been a statue of The Franchise right outside the rotunda.

Instead they waited until Seaver was diagnosed with dementia to say there was a statue underway.

Now that Tom was unable to make public appearances when they changed the address of Citi Field to 41 Seaver Way.

Tom Seaver retires from public life: March 7, 2019

Tom Seaver statue plans revealed: March 8, 2019Tom Seaver death announced: September 2, 2020

Tom Seaver statue ETA announced: September 3, 2020Absolute bang up job by the Mets in honoring the best player in their history

— Richard Staff (@Staff7998) September 3, 2020

That’s sarcasm, by the way.

If there is any silver lining today, it’s that the Wilpons are on their way out. The Madoff chickens have finally come home to roost, and now Steve Cohen, a man who grew up rooting for the Mets, will soon own the team.

I expect that part of his mission will be to find creative ways to repair the relationship between ownership and the current generation of the New Breed. I have lots of ideas, as I am sure great Mets historians like Greg Prince, Matt Silverman and Brian Wright will have as well.

Mine is pretty sizable, and will require a lot of courage and cash.

Dear Steve Cohen,

There are many wrongs that need to be righted when you take control of our beloved #Mets. I hope you consider this request.

Rename our ballpark “Seaver Field”

Love, your pal, Heals

Let’s get #SeaverField trending, #MetsTwitter

— Mark C. Healey (@MarkCHealey) September 5, 2020

Seaver Field.

A Seaver statue that actually gets built.

The fans have always loved Tom Seaver, but he deserved better from the ownership of the team that he helped transform from a national joke to a Miracle. It’s time to set things right.

Rest in peace, Tom. You will always be in our hearts.